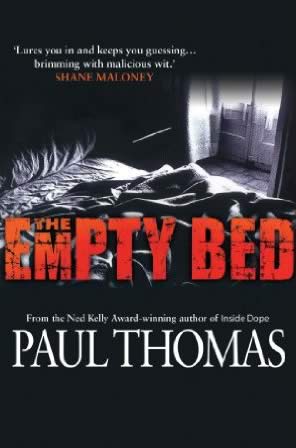

The Empty Bed

Chapter 1

I’m not sure of anything any more. Except this: ignorance is bliss. What we don’t know can’t hurt us. And what we find out can erase our certainties, like words wiped off a blackboard.

You can make up your own mind but, for what it’s worth, I don’t think I deserved it. I followed the rules; I did my best. That’s how I see it most of the time, anyway. Now and again – when I’ve had a few, say - I blame myself. As you do.

I divide my life into BC and AC. C is for cat, the cat that got out of the bag.

We made love the last night of BC. She’d been out – dinner with clients. She had a lot of those. I was in bed pretending to read a book when she got home. She came into the bedroom sparkle-eyed, flushed with drink and flattery. I’d always assumed that these client dinners were frisky affairs. The men would play up, chance their arm, and who could blame them? A woman like my wife beat the hell out of the usual idiot-savant marketing types or some grey-faced financial controller with permanently clenched eyebrows.

She was usually up for it, as they say, after these evenings of wine and flirtation. I didn’t attach any particular significance to that - I gather the same applies to a lot of women. But I had to be quick: once her head hit the pillow, the wine took her down fast. Give her a couple of minutes to nestle in and she wasn’t a taker for that swelling lump nudging her buttocks. She’d murmur, ‘Honey, I’m gone.’ And thirty seconds later she would be, snorting softly as she drew away.

That night, I left nothing to chance. When she stretched out to switch off the bedside light, I slid questing fingers down her spine into the first of the warm splits. She gave a little shudder and said, ‘Oh, like that is it?’ My fingers hurried on, dipping into hot fluid. She said, ‘I’m ready.’ She stayed on her side with her back to me, lifting her upper leg so that the knee was almost touching her shoulder, and fumbling for me. She was as ready as she’d ever been, purring, wide-open, a film of sweat popping on her flared back. I put it down to the wine and the fact that sometimes, for no reason that I understand – hormones? Biorhythms? - lust comes over us with special violence. Afterwards I asked, ‘What got you going?’ but she was already shutting down. She flopped onto her front, subsiding into the mattress, and went to sleep.

Our last conversation BC was less remarkable. In fact, it was mundane to the point of bathos. She was on her way out to play tennis; I was staying in to work. The subject was what we were going to have for dinner. I offered to barbecue and she said, ‘I don’t feel like meat.’ I laugh about that sometimes. I don’t imagine it’s a pretty sight.

I said, ‘We could go out.’

She said, ‘I was out last night.’

‘I wasn’t.’

‘Why don’t we just have pasta?’

I said, ‘I had pasta last night.’

She looked at her watch. ‘I’m going to be late. Whatever.’ She blew me a kiss and walked out, swinging her racquet and her fine behind.

I tried to work. I have everything I need to work at home: the tranquillity of a child-free household in a gracious neighbourhood, a study which gets the afternoon sun, a squat PC which hums with latent power, a wall of reference books. Everything except the will. I go into the study, close the door, and … muck about. The only thing that can keep me in there for more than half-an-hour at a time is getting lost in a maze of pornography while roaming the internet, a doubly unproductive exercise given that the boys I teach hardly need my help to get their gelled and bepimpled heads around that subject.

That weekend I had the excuse of a cold. A pretty good excuse it was too; I had a sore throat, a headache, and a constant flow of oily, olive mucus which meant that I couldn’t leave home without a stack of handkerchiefs. On my way out for a coffee, I went to the handkerchief drawer but my wife had got there before me. She’d been sniffling and dribbling for a few days and had no time for those pointless, lacy scraps with which women are supposed to cope with everything their noses throw at them.

I didn’t make a habit of going through my wife’s pockets but this was an emergency. These days, only urchins and senior citizen street-people can get away with wiping their noses on their sleeves. The hip-pocket of a pair of Dolce & Gabbana trousers gave up an unmarked white linen handkerchief and a folded piece of paper. I suppose some men, some prissy souls, would have put the piece of paper back where they found it and gone sniffing and hawking on their way. It never occurred to me to do that. We had, after all, been married for fifteen years. We were on record as claiming that we didn’t keep secrets from each other, a boast which, now that I come to think of it, usually met with scepticism. So for no other reason than casual curiosity, I unfolded the piece of paper. The period of my life that I think of as BC was about to end. As were a few other things.

It was a note, hand-written: My darling Anne, You are out of this world. I can’t wait till next time. It was signed, if you can call it that, Jxxx.

Nothing too enigmatic about that, I think you’d agree. Not a text which was open to a barrage of jostling interpretations. Needless to say, I couldn’t call on such sardonic resilience at the time.

To begin with, I went into denial. It didn’t make sense: this ‘darling Anne’ couldn’t be my darling Anne. There had to be some explanation - bizarre, perhaps, discomforting, maybe, anything but the catastrophe those words signified at face-value. Our marriage had stood the test of time. We were better at it than most. Many of our married friends were on their second and some of them still hadn’t got the hang of it. And we were more than just quietly fond of each other as couples with sturdy, convenient marriages can be. We loved each other. We said so regularly. Maybe I said so more often than she did but there wasn’t much in it.

Look, I don’t mind admitting that I wasn’t the greatest catch. There were those in my wife’s circle who’d failed to see the attraction 15 years ago so god knows what recent acquaintances made of us. Certainly, if professional status and remuneration were their criteria, they’d have to conclude that she’d married down. She’d long since swerved confidently into the fast lane while I’ve puttered along a dreary back-road these days used only by the timid and the unworldly, my heart no longer in the journey but too far gone to turn back.

I defy anyone in that position not to have the odd spasm of insecurity. I sometimes fished for reassurance in the guise of wry self-deprecation as in, ‘One of these days, you’ll trade me in for a flasher model.’ And she’d smile and shake her head and say things like ‘Where do you get these daft ideas?’ or ‘You’ll do me.’ All the indicators were positive. She was happy. She was flourishing. Life was good. We still had fun. We still had sex. She still enjoyed it.

And then I remembered the previous night, how she’d breathed, groaned almost, ‘I’m ready.’ That wasn’t my doing. I didn’t get her ready - she was already ready. She’d walked in the door with a glow between her legs, wanting more where that came from. But she’d had to settle for me, anything to soothe that burning itch. She hadn’t kissed me, hadn’t even turned her head. She’d just grasped the nearest cock and backed onto it.

I stormed through the house, cursing and shaking. Eventually, I managed to calm down. I had to get a grip on myself; I couldn’t afford to lose control. My wife was formidable in our rare confrontations precisely because she kept her cool whereas I tended to burst into flames. She was skilled at exploiting my combustions. She’d say calmly, ‘Well, if you’re going to be like that, there’s no point in continuing this discussion.’ Or, if I’d thoroughly demeaned myself, her face would set like stone and she’d maintain an arctic silence until I withdrew and apologised. This time, I vowed, I would not overreach myself, I would not lapse into obscene incoherence. There was no need. The thing spoke for itself.

In the midst of this maelstrom of humiliation, self-pity and jittery anticipation, I realised that part of me was deriving a weird kind of pleasure from the situation. I actually blushed. Until that moment, it had never occurred to me that I might have a masochistic streak.

Let’s face it, we all relish occupying the moral high ground, even though it usually involves sacrifice. Up until that moment, nearly all the shameful behaviour within our marriage could be laid at my door. While I’d done nothing which could be termed vile, I had, for instance, ruined Christmas Day for young and old by arguing poisonously with my father-in-law across the table. And as I’ve mentioned, there was a school of thought, in which my wife’s family was heavily represented, which held, in a nutshell, that I wasn’t good enough for her. Exhibit A was my inadequacy as a provider, exhibit B my physical appearance and personality. There’s no accounting for taste but only the radically unconventional could find me a more attractive human being than my wife. This time, though, no-one could point the finger at me. The fault was all hers. The damage was all mine.

My wife didn’t hurry home. Perhaps they were playing Wimbledon rules – no tie-breaks in the deciding set. For all her easy grace on and off the court, she was one of those people who need to win and I found myself wondering if the previous night’s exertions would catch up with her if it ‘went down to the wire.’ That should give you some idea of how disoriented I was.

The waiting got to me. I was spinning out, all appeasement one minute, willing to overlook a posse of lovers, and psychotic the next, wanting to break her neck.

I went for a drive, to fill in time and occupy my seething mind. Ironing shirts was an alternative but, fastidious as I was, that didn’t require quite enough concentration. Failing to give Sydney traffic due respect, however, was akin to autocide and it was a little early to be contemplating that.

I found my way to the airport. There was no conscious decision involved; no mystery either. The urge to trade in my life for a new one in a faraway place was my standard reaction to professional setbacks and domestic unpleasantness. Feeling unappreciated at work, I’d picture myself living off the land among grimy, grinning peasants in some overlooked corner of Europe. After one of our rare, no-holds-barred rows, I’d lay awake in the spare bedroom imagining the man from Interpol doing his painful duty, informing my wife that the trail went cold in Vientiane; it looked like I’d gone bamboo, melted into the jungle or headed up river to places from where white men came back changed out of all recognition - if they came back at all.

This ludicrous fantasy was an old friend. I’d been devising variations on it since I was a teenager. Back then, the basic storyline was a blend of the Charles Atlas sales pitch and Kung Fu – 140 lb weakling spends five cruel years in mountaintop martial arts academy, emerges as wire-hard warrior with supernatural penis. Par for the course, I suppose, for a lonely, mildly fucked up 17 year old. One expects more of 43 year olds, even 43 year old cuckolds in the first flush of humiliation.

A mini-bus pulled up behind me, disgorging a cabin crew from an Asian airline. One of the stewardesses, a willowy beauty, as alert as a wild animal after years of side-stepping bottle-nosed foreign devils at 30,000 feet, examined me gravely as she filed past. I ventured a rueful half-smile but her eyes slid away without a flicker of response and she disappeared into the terminal, dragging her little luggage trolley behind her.

I drove back into town, to the school where I taught. There were plenty of people about, mainly parents and browsing girls come to cheer on their jock sons and boyfriends-to-be. I made it to my study without bumping into any of the tweedy fanatics among my colleagues who regarded time spent in the classroom as an irksome distraction from our true mission - to nurture champions. I was in no mood for their clod-hopping mateyness or their homoerotic raves.

I shut the door and rang my parents, down on the farm.

My mother answered. ‘I thought you’d be watching the game.’

‘Eh?’

‘The big match.’ Christ, I couldn’t get away from it. ‘Your father’s gone over to the Curtises to watch it.’

‘I forgot it was on.’

‘Oh, well.’ There was disappointment in my mother’s voice: sport and gardening were subjects my father and I could discuss calmly, even amicably. I didn’t have strong views on either. ‘Anyway, how are you, dear?’ Without waiting for an answer, she added, ‘How’s Anne?’

I should have expected that. Unlike me, my wife had never suffered the Chinese water torture of parents-in-law’s disapproval. My mother admired her as wholeheartedly as everyone else did. It brought home to me, though, that this was a pointless exercise. My parents couldn’t help me. This sort of ugliness didn’t feature in their lives; it was something that happened to other people, unsound people. Besides, trouble on the home front was a matter for one’s vicar. He had the answers at his fingertips.

‘We’re okay. Look, sorry Mum, but I’m actually at work and someone’s just walked into my office. I better go. Talk to you soon, okay?’

‘All right, dear. I’ll tell your father you rang.’ She wasn’t put out; she was of a generation who accepted that work came first. ‘Give our love to Anne.’

You bet. I’ll slip it into the conversation first chance I get.

I rang my sister at the waterfront dream-home she shared with her husband, a sleek financier with the Midas touch, and their three pulverisingly loud children. Rosie allowed me to flounder through a conversation with her seven year old – ‘So, Arabella, what have you been up to today?’ ‘Are you being nice to your little sister?’ – before coming to the phone. I was sufficiently deranged to tell her what I thought of parents who encouraged their toddlers to answer the phone.

‘Thank you for that,’ she said sweetly. ‘Was there anything else?’

‘It happens to me all the fucking time. I mean, if I want to talk to Arabella, I’ll come over and …’

‘What’s the matter, Nick?’

‘It’s Anne.’

‘What’s happened?’ It came out in a rush. Rosie and Anne were more like sisters than sisters-in-law.

‘I think we’ve got a problem.’

‘What sort of problem?’

‘The sort that involves a third party.’

There was a long silence before Rosie said, ‘Oh god, you don’t think Anne’s having an affair, do you?’

‘I think it’s a distinct possibility.’ When she didn’t say anything, I said, ‘Aren’t you going to tell me it’s out of the question?’

‘I’ve seen too many apparently rock-solid marriages go belly-up to say that about anyone, even Anne. So what set this off?’

I lied. I told her there was nothing concrete, I just had a nagging suspicion. And I didn’t pay too much attention to her advice which consisted of a string of banalities, rattled off as if she could smell something burning: I shouldn’t jump to conclusions, maybe it was just a communication thing, Anne wasn’t that sort of person, she was probably under pressure at work.

My sister couldn’t help me either.

I sat at my desk. Nothing moved except my brain. For the first time since I’d found the note, I thought beyond the betrayal and the looming confrontation. I thought about the consequences.

Was this it for us, was this the end of the line? Well, that could be up to me. Getting back to tennis for a moment, the ball was in my court. Could I live with it? Could I forgive her?

I’m not a hater and I don’t bear grudges. I don’t have the energy. I’m not saying I like the creeping jesus who brown-nosed his way into the head of department’s job at my expense but I don’t sit around thinking of ways to get my own back. If short-fuse Steve throws a tantrum on the golf course or tight-arse Tom brings a cheap bottle of wine to our dinner party, I might let them know I’m not impressed or I might let it slide. Life’s too short to be always taking offence.

But this was different. This was one step down from life and death. It seemed unlikely that both our marriage and my self-respect could come out of it intact. Something would have to give. And even if I ate shit, would that see us through? Maybe the condition was too serious to respond to a change of diet, however radical.

Then again the hard line didn’t have much going for it either: starting over, living alone, being the only single at dinner parties, getting tagged as a social cripple or a closet queen … The prospect of having my life turned upside down and shaken out was terrifying. If push came to shove, I could get by without my self-respect but I had precious little confidence in my ability to get by without Anne. Her fingerprints were all over my existence, from the flower arrangement in the hallway to the biennial lunch at our favourite restaurant in the 16th arrondissement. Was I tough enough to walk away from that?

As my pupils say, ad nauseam, I don’t think so.

This excerpt is from Paul’s 2002 book The Empty Bed.