Death on Demand

PROLOGUE

WARREN

GREYTOWN

THIRTEEN YEARS AGO

Females had always found him hard to resist. When he was small, his aunts and cousins cooed and fussed over him, telling him how gorgeous he was. His older sister was like a second mother: she spoilt him, couldn’t stay mad at him, wouldn’t let him leave the house without a hug. Other kids, their sisters called them retards and wouldn’t touch them without rubber gloves.

At 13 he had a growth spurt, and suddenly wasn’t a cute little boy anymore. Now his aunts went on about what a handsome young man he was becoming. When the phone rang in the evening half the time it was girls wanting to speak to him which made his old man huff and puff. Once he overheard his sister on the phone: “Forget it, bitch,�? she said. “He’s way too young for you. I don’t give a shit that his balls have dropped, he’s still only fourteen. Let me explain something: I worry about my sweet little bro. I worry about him getting pimples and an attitude and turning into a dropkick; I worry about him getting in with a bad crowd and leaving school with nothing to show for it; I worry about all sorts of things. But most of all I worry about my slut friends getting their slutty little claws into him and putting him off girls for good.�?

Around that time his parents had a party. He helped out pouring drinks, picking up empties, slipping coasters under glasses left on the sideboard. This woman he hardly knew kept staring at him. Next time he came by with a bottle of sauvignon blanc, she waved her empty glass. He went over. She manoeuvred him into a corner, standing right in front of him with her back to the room. It was weird: she was his mother’s age and spoke to him like adults usually did, asking pointless questions – “So what’s your favourite subject?�? – and not listening to his replies, but she kept touching him, squeezing his bicep and stroking his forearm. Her face was so close her breath warmed his cheek. Her leg pressed against his.

He squeezed past her, saying he had to get some more wine. She followed him into the kitchen, eyes bright, lips curved in an unsettling smile. She pushed him up against the bench. Her mouth fell open as she reached out to pull his face down to hers. He tasted wine as her tongue flailed around inside his mouth. Footsteps in the corridor made her pull away. A guy came in looking for beer, and as soon as they started talking he slipped out the back door and ran down the street to a friend’s house. He didn’t tell his mates; they gave him enough shit about being a pretty boy as it was. Besides, they would have thought it was gross, some old bag sticking her tongue down your throat.

She was really friendly next time he saw her. Thinking about it that night, he decided it was probably because he’d kept his mouth shut: in Greytown gossip circulated at the speed of sound. He was tempted to knock on her door one morning after her husband had left for work just to see what would happen, but there was a fair chance it could backfire, big-time. He was curious, but not that curious.

He wasn’t academic, but he was worldly by the standards of Greytown teenagers and had grown up with an older sister. He lost interest in girls his age pretty quickly. He tended to lose interest in girls younger than him before their friends had finished asking him to ask them out. He gravitated towards older girls, but the smart, sparky ones took off as soon as they’d left school, whether to go to university or embark on life’s big adventure.

Craig and Donna came up from Wellington to run one of the cafes which had sprung up along the main street. They rented the house next door while the owners, empty nesters, went travelling for a year. There was a party every weekend which ruffled his parents’ feathers, but he got on fine with them and scored a part-time general dogsbody gig at their café.

He got on particularly well with Donna who he guessed was in her mid 20s. She’d lived in Sydney for a couple of years and bummed around Asia, sleeping on beaches, smoking weed, doing Buddhism for beginners. The problem with the girls he went out with was that they didn’t know how much was enough, so they showed too much thigh or too much tit or were too eager to please, trying to swallow you whole when they kissed or sucking your dick without being asked and probably without wanting to because they didn’t want to be labelled cockteasers. He actually didn’t mind a bit of cock-teasing; it added to the fun, gave you something to look forward to. Donna made them seem very young: indiscriminate, compliant little herd animals. She had a way of triggering a rush of longing with just a look, a sideways smile, a murmured aside.

Not that he had great expectations. For a start, she was a woman and he was a boy. A good-looking, rapidly maturing one perhaps, but still a boy. Secondly, she was living with a guy. She laughed when he asked if she and Craig were married – “Oh yeah, that’s me: good little wifey�? – but she wore a ring and they seemed as much of a couple in their interaction as most of the husbands and wives he’d observed. And while Craig treated him okay and took the piss in that blokey way, he had the look of someone you wouldn’t want to cross.

His bedroom window looked out onto his father’s vegetable garden and into next door’s spare room where Craig had set up his weights. One day he was idly watching Craig pump iron in front of a mirror with his shirt off when Donna appeared in little shorts and a tight singlet. He kept watching, but closely now. Suddenly Craig got up off the bench and came over to the window. He gave him a weak grin and a wave; Craig held his expressionless stare for five seconds, then squeezed out a thin smile. Next day at the café Donna told him he should feel free to come over for a workout if he ever got the urge. He blushed and started to apologise, but she grazed a fingernail down the side of his face. “It’s okay, baby,�? she murmured. “It’s cool.�?

He sometimes wondered what she made of Craig’s habit of laying a heavy dose of charm on any attractive woman who came into the café. This particular day he was behind the counter watching Craig do a number on this woman from Carterton who’d started coming in on her own pretty regularly. Suddenly Donna was standing right behind him, resting her hand on the small of his back.

“Look at that wanker,�? she said. “He thinks he’s irresistible. You could teach him a thing or two.�?

He turned his head to look at her. She was so close they were almost bumping noses. “What about?�?

She gave him a lazy smile. “Oh, you know, how to look at a woman. Raw lust doesn’t do it for most of us, any more than being taken for granted. We like to see a little tenderness.�?

Then without warning, without saying goodbye, without a word to anyone, Donna and Craig were gone. It was the shock of his young life: he was used to deciding when a relationship’s time was up, as opposed to having it decided for him. Whatever there was between him and Donna was undeclared, unfulfilled and at least partly in his head, but it was more real and more significant to him than any number of teenage pairings with their juvenile rituals and matter-of-fact sex. And while there was an element of fantasy, it was a fantasy she’d encouraged. He hadn’t imagined that. He was crushed that she could leave him desolate, without a word or gesture to acknowledge the depth and purity of his infatuation.

It turned out that they’d skipped on a raft of unpaid bills, including several months rent. His mother went into I told you so mode, insisting she always knew they were fly by nighters, there was just something about them, good riddance to bad rubbish. His Donna thing hadn’t gone unnoticed by his contemporaries. Boys who’d had to make do with his sniffling cast-offs and girls he’d ignored or casually dumped delighted in telling him he’d made himself look ridiculous, having a crush on a woman who obviously didn’t give a shit.

His old man, of all people, was the only one to shed any light. Donna and Craig were chancers, he said, drifting from place to place looking for an arrangement, a set of circumstances, which worked for them; when it didn’t materialise, they moved on. Because they never stayed in one place long enough to form real relationships, it didn’t bother them to run out on their debts or abandon people who thought of them as friends. That set his mother off again: they were common criminals, she snorted; it was just a matter of time before the police caught up with them and they got what they deserved.

He hardly slept that night. Now he got it. Why would they stay in Greytown? What would keep them there? It was a place you had to get away from, and that’s what they’d done. No explanation, no apology: when it was time to go, just disappear without a trace. That way you could start again somewhere without having to worry about the past - people who’d passed their use-by dates, pain-in-the-arse complications - stretching out its long, bony arm to tap you on the shoulder.

Another couple, gays this time, took over the café. It was just drudgery now, but he stayed on because he needed the money for what he had in mind. A week before the end of the school year, he got a letter, care of the café. It was from Donna. She was sorry for taking off like that, but things had got messy and they’d done their dash in Greytown. He had to get out of there, she wrote, or he’d end up just another drongo stuck in a shit job, living a shit life. If he made it to Auckland, he should check out the Ponsonby café and bar scene: if she was still there, they were bound to bump into one another sooner or later. There was a PS: burn this and don’t tell anyone you’ve heard from me.

His plan firmed up. His parents were spending Christmas and New Year in Mount Maunganui with the in-laws; a couple of his mates were going down to Wellington to watch the cricket test at the Basin Reserve. He told his parents he was going to the cricket and would crash on the floor of a friend of a friend’s flat; he told his mates he’d ride with them down to Wellington but peel off to go camping in the Sounds with his sister and her boyfriend.

His mates dropped him off on Lambton Quay. He lugged his bag to the train station and bought a ticket to Auckland. He left without warning, without saying goodbye, without a word to anyone.

JOYCE

ST HELIER’S, AUCKLAND

SIX YEARS AGO

It all boiled down to self-discipline. Sure, being organised helped, but a lot of what people called organisation was really self-discipline: having a structure to your life; sticking to your plans and routines regardless of what circumstances and other people threw at you. Having a few brains helped too, but less than you’d think. Look at her: nobody’s fool, no question about that, but certainly no Einstein. She came across plenty of people who were brighter than her. For that matter some of her employees were brighter than her. So how come they worked for her and not the other way round? How come she was more successful than all those brainboxes out there? Two words: self-discipline.

She did her stretches at the bottom of the drive, glancing up at the dark mass of the house.

Where would our lovely home be without my self-discipline? Gone west, that’s where.

Self-discipline had got her through a degree while holding down a full-time job. Self-discipline had enabled her to raise two well-adjusted, high-achieving kids while working part-time. And self-discipline had been the key to building a thriving business from the ground up when their comfortable little world was on the verge of falling apart.

It was 5.59 am. She shook the traces of sleep stiffness from her arms and legs, set her watch, and eased into a jog. Within 25 metres she was moving at the brisk tempo she’d maintain for the next three-quarters of an hour.

Self-discipline had enabled her to roll back the disfiguring effects of childbirth without resorting to cosmetic surgery, like some people she could mention. To heck with that: this body was all her own work. And pretty darn trim for 51 if she said so herself, as she often did when she inspected it in the full-length mirror in her walk-in wardrobe.

Self-discipline got her out of bed at 5.40 every second morning to go for a run. Even on mornings like this when the mid-winter chill turned your nose red and your fingers white and it would be so easy to sink back into that big, soft bed. Even if she’d been up late getting on top of her paperwork, or cleaning up after a dinner party while her husband was upstairs snoring his head off. Assuming he was capable of negotiating the stairs. Even if she had a rotten cold, because you couldn’t let a little bug rule your life. Every second morning, without fail, she was down at the gate stretching by 5.55 and on her way by six. You could set your watch by her.

Her route never varied. What was the point? It was exercise, not sight-seeing. Mind you, she’d be doing the old eyes right when she passed a certain house that had just gone on the market, a snip at $8.7 million. Dream home was right. Dream on. Not that they couldn’t have done the deal. Since the business took off, getting money out of the bank was the least of her worries - they were almost offended that she didn’t want more. Once bitten, twice shy though. She had nothing against bankers – well, nothing much anyway - but she didn’t want them owning a chunk of her home. When you own it outright, no-one can take it away from you.

If it was up to her husband, they’d be moving in next week. He still didn’t get it even though it was his over-confidence and, let’s face it, lack of self-discipline that had landed them in the poop in the first place. Oh well, he was what he was and that leopard certainly wasn’t going to change his spots. Besides, she wouldn’t have fallen for him if he’d been a different person, more like her. They were a classic case of opposites attract. No, it wouldn’t happen next week, but it would happen. And the first he’d know about it would be when she tossed him the front door key and said, ever so casually, “Darling, you know that house in Lammermoor Drive that we were so keen on….�?

People couldn’t believe she went jogging without an iPod. What a waste, drifting through this precious, uninterrupted time with your head clogged up with music. This was when she did her best thinking.

Maybe she would have checked before crossing the road if she hadn’t been preoccupied with the looming confrontation with her increasingly distracted personal assistant. Maybe she would have noticed the car if the driver had had his headlights on. But there was so little traffic at that hour of the morning in those leafy suburban streets.

By the time the engine noise did penetrate her cocoon of concentration it was too late. She was in the air for several seconds, her body a bag of shattered bones, her limbs as limp as a rag doll’s, because death was instantaneous.

EVELYNE

REMUERA, AUCKLAND

NINE MONTHS AGO

They were two of a kind, she thought: stubborn old bitches.

She looked down at the Golden Labrador lying at her feet. Beth just pipped her age-wise, 15 dog years being 90-plus in human terms, according to some chart her daughter had found on the internet. They were really just hanging on because the alternative – slipping away into oblivion – was even less appealing.

They still had their marbles, thank God, but were a couple of physical wrecks. Now and again the woman who did her shopping and cleaning tried to interest Beth in a walk around the block, but after 50 metres or so she’d just lie down on the footpath and refuse to budge. A far cry from the days when she followed you around like a shadow until you gave in and got the lead, then dragged you through Cornwall Park practically ripping your arm out of its socket.

As for her, the stairs were her Berlin Wall, a barrier to the outside world. Going down was manageable but, Lord above, getting back up. Her son’s solution was for her to move into a ground floor apartment or a ‘unit’ – what an evocative term for home, sweet home – in a retirement village. Not on your Nellie, buster. She’d lived here since 1968 – they’d actually signed the contract the day the Wahine went down – and moving now would seem like a repudiation of the best years of her life and the memories that sustained her. She wasn’t going anywhere; they’d have to carry her out in a wooden box.

Her solution was much more elegant: install a basic kitchen upstairs, convert one of the spare bedrooms into a living cum TV room, et voila: the stairs were no longer a problem because there was no reason to go downstairs. Someone asked her if she ever got bored being restricted to one floor. What a daft question. House-bound was house-bound: what difference did it make how many rooms your world has shrunk to? Besides, boredom was as much part of old age as loneliness and infirmity, although it didn’t get as much recognition.

By and large she’d learned to live with loneliness. The only way she was going to see her husband was if he was waiting for her on the other side. Much as she’d like to believe that, and much as she’d like to think her decades of conscientious church attendance would be rewarded, she wasn’t taking it for granted. If there was an afterlife, she hoped her mild scepticism wouldn’t be held against her.

She always went along with her friends’ suggestions that she must miss the entertaining, but that was for their benefit: they would probably be offended if she disagreed. In fact she didn’t miss it at all. It was something she and her husband had done together: he loved planning a dinner party, putting together a menu, organising the food and wine, and his enthusiasm rubbed off on her. And in those days she had a decent appetite and liked a glass of wine or three. Now she ate like a bird and a second glass of wine left her feeling as if she’d been sandbagged.

She missed her daughter and grandchildren - and son-in-law up to a point - but they lived in Brussels. Their visits every second Christmas were, by some distance, top of her ever-diminishing list of things to look forward to. Her son and daughter-in-law lived on the North Shore. Of course she enjoyed seeing them, but if she was absolutely honest it wasn’t the end of the world if he rang to say they were too busy to make it over that week. Maybe she was being unfair, but when they did come she always got the feeling they’d spent the drive over working out why they couldn’t stay for very long.

The truth was the relationship hadn’t been quite the same since she’d politely but firmly rejected her son’s suggestion that he should take over the running of her financial affairs. It was for his own good, not that he could see that. Despite ample opportunity he had failed to demonstrate that he’d inherited his father’s astuteness in money matters. A couple of her husband’s friends, who did share his astuteness in money matters, were happy to look after her affairs and had done a very good job of it. Unlike some other widows she knew, she’d come through the recent financial turmoil relatively unscathed. When the time came her son could do as he pleased with his share of the inheritance, and if he didn’t, his wife certainly would. The look on their faces that time she jokingly suggested she might leave a decent whack to the SPCA… Clearly there were some subjects one simply didn’t joke about.

Goodness gracious, what was that racket? Beth really was on her last legs if she could sleep through that. It was one of those dreadful radio people being inane at the top of his lungs. Why were they so proud of being imbeciles? It sounded like it was coming from downstairs but her help had left hours ago and anyway wouldn’t have dared to put talkback on at that volume. It had to be some kind of electrical fault or power surge. Oh well, nothing else for it but to venture downstairs for the first time in months.

Leaning on her walking stick, she made her way to the top of the stairs. What a god-awful din. She thought of trying to find the ear plugs she used to block out her husband’s snoring. He, bless him, claimed it was all in her mind.

She lurched forward, losing her balance. The landing rushed up to meet her. Her last thought was to wonder if that loud click that seemed to come from inside her head was the sound of her neck breaking.

LORNA

PARNELL, AUCKLAND

ONE MONTH AGO

She had to clasp the cup in both hands to stop it spilling, and it clattered in the saucer when she put it down. The man at the next table was staring at her. She could feel his prying gaze roam over her like a torch beam. She could almost hear his eyebrows clench as he observed her burning cheeks and shaking hands and the mess she’d created – the puddle of milk, the dusting of sugar. She trapped her hands between her thighs, where they couldn’t shake and couldn’t be seen, and looked straight ahead. Everyone in the café must be looking at her thinking, what’s going on there? What’s up with the woman of leisure in the Trelisse Cooper outfit and the Blahnik shoes?

It was a good question. What the hell was she doing there? Why was she, a sensible, enviable, middle-aged married woman who’d hardly done a reckless or wilfully foolish thing in her life, sitting there summoning up the nerve to go into the apartment building across the street and have sex with a man she barely knew? Why would anyone in her position and in their right mind even contemplate it?

Because while her husband doted on her (which, in his mind, was proof of love), he wasn’t really interested in her as a person. He was solicitous, respectful, indulgent, but never sought her opinion on anything beyond trivial domestic or social matters, and struggled to conceal his indifference whenever she volunteered it. He was happier to go to work than get home, happier to hook up with his male friends than stay with her.

Because there was more to life than lunches with other ladies who lunched, and tennis, and yoga classes, and charity work (socialising by any other name), and overseas holidays, and supervising the gardener.

Because the children had left home.

Because she was ashamed of not having done more with her life, in the sense of using her ability and exposing herself to a wider range of experiences and challenges.

Because it was too long since she’d had an adventure.

Because she was bored.

Because she wanted to have a secret, something thrilling and forbidden she could relive second by second when she woke up at three in the morning.

Because when it was over she could walk away, knowing there would be no aftermath, no repercussions.

Because there was no risk.

She finished her coffee. Her hands had stopped shaking. She placed her palms on her cheeks. They were warm as opposed to hot, which meant pink as opposed to crimson. Pink she could live with.

She stood up and walked out of the café, not caring if people were staring at her, feeling the first, faint stirrings of arousal.

CHRISTOPHER

ST HELIERS, AUCKLAND

TWO WEEKS AGO

He’d always wondered how he’d react if it came to this. Pretty well as it turned out, assuming you subscribe to the code of the stiff upper lip. Quite the stoic, in fact. He hadn’t swooned or broken down or got angry; he’d sought clarity on the time frame and, as the condemned often do, thanked his sentencer. The specialist had admired his courage, belated acknowledgment that he was a patient rather than a case study.

It was a different story at home, of course. He’d thrown up, he’d howled and ranted, he’d soaked his shirt front with tears like equatorial rain drops. When the crying jag had run its course, he stared at himself in the mirror above the basin. A Latin phrase he hadn’t used or thought of since boarding school popped into his head: Morituri te salutant – those who are about to die salute you. He seemed to remember it was what the gladiators said to the emperor before hacking each other to bits for his entertainment.

He sat beside the pool drinking $300 a bottle cognac. Buggered if he was going to leave that for the wake. When the sun went down he went inside and passed out on the sofa. He woke up with a quiescent head in a room stuffy with sun having slept for 14 hours. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d managed ten; probably not since his student days. It was a fine time to regain the knack of sleeping in.

He thought about telling his friends, but that could wait. There was nothing they could say or do and he wanted to put off being treated as an endangered species for as long as possible. They would ask, “Have you had a second opinion?�? This was the second opinion - and third, fourth, fifth, and sixth. The best people in the field in Australasia, doyens and young Turks, safe pairs of hands and pushers of the envelope, optimists and pessimists, had read the notes and studied the images. They were unanimous: It’s inoperable. It’s terminal. Time is very short. We are very sorry.

He would put off telling the kids for as long as possible too. They were both overseas and there was no point in deranging their busy lives any earlier than necessary. That was how he rationalised it anyway. The real reason was that their grief would be intolerable.

He thought of getting in touch with his ex, just out of curiosity really. Would she feel guilty about the way she dumped him, without warning or sympathy? Would she offer to nurse him? He suspected the answers would be no – she simply didn’t do guilt, that one – and yes. She’d probably want to be involved, not because he meant anything to her, but because she would respect the fact that he was dying. But he wouldn’t have that. No matter how bad things got, he wouldn’t have that.

There was only one person he yearned for, one person he wished he could cling to in the night, but she was out of reach. He’d made sure of that.

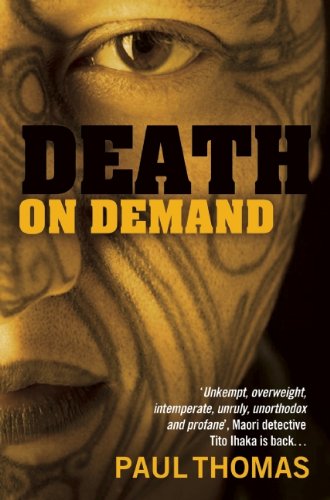

This excerpt is from Paul’s 2012 novel Death on Demand.